|

British documentary On the Road to Dallas premiered at the 16th annual CaribbeanTales Film Festival- an enthusiastic entrance within the Women in Resistance programme. With a strong women presence, this film shatters norms forcefully imposed on femininity, through the expression of pure and undisrupted joy. Power can manifest in any mode – even in rollerblading. © CTFF Directed by Mathilde Marinet, On the Road to Dallas tracks the story of sixteen, UK based, West Indian women striving to make their mark at a roller derby competition. Throughout the journey, they open up their hearts and find unexpected community in one another. Themes of fellowship, identity, and passion are explored within this film, as the women embark on a journey to win the esteemed World Cup. With a quick pace and constant state of movement, it is easy for any viewer to feel overwhelmed; however, On the Road to Dallas effectively keeps the viewer engaged with its clear, precise film structure. The film is carefully, and successfully, crafted into three acts – setting up the members, the prepping for the World Cup, and ultimately, the World Cup itself. This composition allows for the viewer to feel as if they are travelling with the members themselves. The story guides us through all of the factors, emotions, excitement, and fears that accompany travelling to and participating in a competition, far from home. The central conflict of the story is simple; everyone wants to win, and no one wants to get hurt. These high stakes are even more increased whilst watching the aggressive bodily contact – this high level of adrenaline can automatically make the viewer grasp at their chair a little tighter, knowing that the consequences of a misstep is either losing or physical harm. In contrast, however, there is a certain level of safety that a viewer can feel while observing this story – it keeps us locked in by genuinely being really fun, authentic, and feeling like a safe space. The authenticity of the characters remains consistent throughout the film - they feel very familiar and relatable, and they are people that I’m sure anyone would want to build a community with. The film brilliantly cuts between the quick, upbeat pace of the story, to intimate moments. The masterful contrast between energy and intimacy produces dynamics, allowing a simple topic to be even more complex than imagined. The structure of shots during the interviews was very visually appealing – the blend of medium wide, medium close-ups, and close-ups contributes to the various layers of the interviewees. The film is also rather bright; there is never a time where the subjects are blending in with their surroundings. “The masterful contrast between energy and intimacy produces dynamics, allowing a simple topic to be even more complex than imagined.” In terms of sound, there were various points where statements were hard to hear. The inclusion of subtitles would have provided clarity, as the noisy setting of the roller derby as a background for interviews was considerably distracting from what was said. The music also overpowered some subjects near the beginning of the film – adjusting the noisy location of the interviews would make for more comprehensible statements heard by the subjects. The range of femininity is superb within this story. Through breakdowns of identity, the women in this film further prove that patriarchal norms of womanhood are subjective. This story debunks a false notion that has been upheld by society for as long as we can remember; femininity can indeed make room for strength, fierceness, and power. Editor’s Note: On the Road to Dallas screened at the Caribbean Tales Film Festival ’21, as part of the Women in Resistance programme.

TIFF ’21 Mlungu Wam (Good Madam): Post-apartheid South Africa and the horrors it left behind9/13/2021

By Nelie Diverlus “A vivid, strangely thriller” is one way of describing Mlungu Wam (Good Madam), which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival ’21 at their opening night Platform programme. This story encompasses a young mother, Tsidi, reeling from the passing of her grandmother. With no other choice, she sets out with her daughter to stay in the residence of her own mother, who is a housekeeper for a woman they refer to as, “Madame”. With strange, unexplained occurrences surrounding her in the house, Tsidi begins to question if she and her daughter can actually feel safe in this house, or if they should find the means to leave as soon as possible. With the systemic issues mentioned in this story, this film illustrates the true day-to-day horrors that Black people, most specifically Black South-Africans, face to this day This story is a marvellous illustration of the aftermath of apartheid in South Africa. Protagonist Tsidi has her suspicions raised throughout the film’s entirety; she is already unapproachable, considering she has to be in the presence of her estranged mother. When the presence of “Madame” is making her question the wellness of her mother (considering she works tirelessly to provide for her), Tsidi increasingly questions the safety of this home, comparing the sight of her mother overworking to the apartheid. South-African director Jenna Cato Bass successfully introduces us to cinema beyond our North American understanding of film. A new dawn of thriller has landed, as Bass stems inspiration from Jordan Peele and Ousmane Sembène, in centering the actual day-to-day horrors living as a Black woman in South Africa ensues, rather than other horror figures that have no social relevance. The centering of real-life horrors - makes the film ever more unsettling, as this adds more relatability to the story – a great fear of any horror movie viewer. “The centering of real life horrors makes the film ever more unsettling, as this adds more relatability to the story – a great fear of any horror movie viewer.” As far as visuals go, this film definitely does not disappoint. The glorious hues of browns, blues and yellows adds a level of royalty to an already regal setting where the story takes place. In addition, the presentation of glass and porcelain at countless points in the film increases the stakes and tension of the story, considering they are very fragile and easily breakable. In contrast, however, the numerous extended shots of ordinary objects (while beautifully framed), practically go nowhere, leaving the viewer empty with extra footage that does not contribute to the story. Order and cleanliness are great themes of this story; down to the shots of scrubbing and washing, and even the arrangement of picture frames and artwork, the viewer can see that there is never room for mess. This supports the housekeeper narrative that is perpetuated throughout the film, and while mess is condemned, disobedience is disciplined. Furthermore, sound also marvellously projects this story forward. The spiritual elements of the film are supported by chanting that increases in volume. While this film was visually captivating, this film’s resolution was far too unresolved for one to take in. The story was left open-ended, leaving the viewer with many more questions than they entered with. Everything, supposedly, gets quickly answered within the last ten minutes of the film, suggesting that the story opened more doors than they could close. One can be rather confused upon finishing this film – nothing really gets answered. “While this film was visually captivating, this film’s resolution was far too unresolved for one to take in.” Mlungu Wam properly evokes relatability with this story – the eeriness of racism and social inequity is increasingly hard to fathom, and this film effectively divests in this. Themes of family and connection are properly explored in this film, allowing the viewer to relate to that similar feeling of hoping for a better life for your loved one. This film teaches us that horror and thrillers extend beyond conjured fables; everyday realities for the marginalized are horrors within themselves.

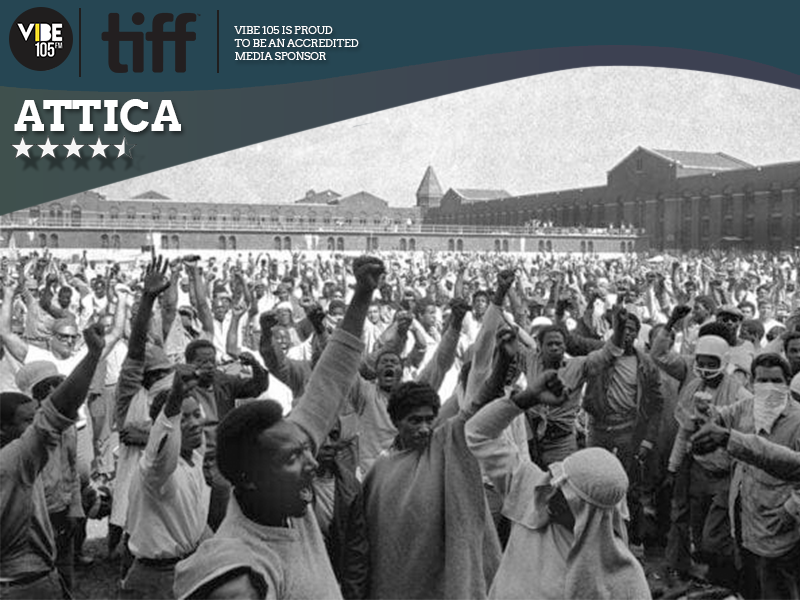

Editor’s Note: Mlungu Wam (Good Madam) screened at the Toronto International Film Festival ’21, as part of the Platform programme. By Nelie Diverlus The TIFF DOCS programme of the 46th annual Toronto International Film Festival debuted an intensely impactful film: Attica. This story centres around the 1971 prison riot at the maximum-security prison, Attica Correctional Facility. By speaking to various survivors of the revolt, along with the family members of the deceased, this film illustrates the targeted state violence that ensued during the late-20th century – the same cruelty that is perpetuated to this very day. Attica effectively sets the scene for its viewers; those incarcerated are simply wishing to be seen for who they are beyond their sentencing. The living conditions within the prison walls were unsustainable, they were being mistreated, and were constantly silenced. The film dives deeper into the brutal and gruesome events that took place during the four days of the riots, and profound statements are heard from the (formerly incarcerated) survivors of the rebellion, along with some of the family members of the deceased. Stanley Nelson has an extensive history of working on creative pieces of liberation, revolution and freedom, and this is presented magnificently within Attica. The energy of this film is palpable; all five senses are engaged while following along with this brutal story. Nelson flawlessly keeps the stakes at a high, leaving the viewer hoping for a resolution to the narrative. One can practically taste blood, smell the foul scents, hear the cries, feel the pain ensued, and ultimately, visualize the true atrocities that took place. “Nelson flawlessly keeps the stakes at a high, leaving the viewer hoping for a resolution to the narrative.” This film does an incredible job at varying the pace of the film in a precise, non-distracting manner. The composition of interview statements, juxtaposed with the impressive blend of found footage, reinforces the anxiety and worries felt while observing this story. The lighting of the interviews is notable – the survivors are seen and heard clearly; a thought unimaginable considering they have been silenced for a considerable amount of time. The aerial shots of the prison are framed marvellously, especially considering the contrast in framing a site of atrocity in a visually and aesthetically appealing manner. While the soundtrack and soundscape are tremendous, it is also worth noting how the beginning started off slightly rocky with sound – the roaring sirens suppressed the voices of the subject, but thankfully this was minimal. The captivating soundscape makes up for this blunder, as this appealed to the senses and had the viewer feeling as if they were a first-hand witness of the monstrosities. The music also effectively transports us to the time era; in the viewer’s eyes, it was no longer 2021, but rather 50 years prior. “The composition of interview statements, juxtaposed with the impressive blend of found footage, reinforces the anxiety and worries felt while observing this story.” Additionally, pattern is a distinct element within this film; various statements are shared amongst the interviewees, helping support solidarity as a large theme of this feature. The soundscape is also explicit and very descriptive in its nature, and stunningly raises the tension mentioned in this story. “The soundscape is also explicit and very descriptive in its nature, and stunningly raises the tension mentioned in this story.” Watching this film releases the unknown radicalism in a great deal of us. The end statements remind us of the standards of living a sustainable life on this earth – standards that are constantly dismissed and forgotten. This film stunningly uncovers the truth of what occurs within prison walls and works to lend a voice to those that have been forced into silence. The feelings of despair and hopelessness felt while viewing this film are clearly intentional, but also genius – this film properly ignites a fire in all of us to continue working for and supporting the voiceless in liberation, revolution, and freedom. “This film properly ignites a fire in all of us to continue working for and supporting the voiceless in liberation, revolution, and freedom.” Editor’s Note: Attica screened at the Toronto International Film Festival ’21, as part of the TIFF DOCS programme. Limited press material supplied by TIFF.

The Shades of Tolerance programme of the 16th annual CaribbeanTales Film Festival introduced yet another moving film surrounding great love and great losses: Right Now I Want to Scream: Police and Army Killings in Rio – The Brazil Haiti Connection. This film recounts, stories from the family of those murdered at the hands of police.. Trauma and anguish have many layers - and this film is designed to dive deeper into them. The story kicks off with a beautiful montage of Brazil’s landscape. Various compositions of movement - including dancing, sports, recreation, and pedestrians walking, illustrate the effervescence of the streets of Rio. Life and mortality are shown to be great themes within this film, especially when contrasting with the harrowing message projected throughout. The decision to have both contrasting clips follow one another is rather intentional; vivacity and livelihood for the victims of police brutality were torn away from them, and this story effectively conveys this. The choice of setting for this film is rather crucial – with an increased general knowledge of police brutality in North America, it is imperative that viewers also divest their attention to the cries of those affected by a brutal police force in other marginalized communities (with a notable large, Black presence). This film touches on the dangers of over-policing, and the implications imposed on communities that are deemed “worth punishing”. Ambiguous notions of good vs. evil is what has allowed for the validation and continued presence of police force - this film challenges that. “Ambiguous notions of good vs. evil is what has allowed for the validation and continued presence of police force - this film challenges that.” Directors Cahal McLaughlin and Siobhán Wills have sturdy ties to this story, as this film builds upon a previous film, they both directed - It Stays with You: Use of Force by UN Peacekeepers in Haiti (2018). Mentions of the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUSTAH) are credited in both films, reinstating the shared themes of life and mortality. The raw emotion seen from the subjects, while gut-wrenching, speaks to the humanity of the viewer and keeps them engaged. Watching the subjects speak felt tugged at the empath within me – I saw my own mother and father on the screen. The love and care shown by the parents of the deceased left me in a fearful state, knowing how much injustice can tear families apart, and I was left wondering if I would even have the strength to express my trauma to a camera. This film effectively instills the fear in all of us with loved ones – how much longer until it is our story that is told? In contrast, in terms of formalities, this film does not quite meet the bar. Sound proved to be a great distraction while watching, leaving me wondering if the sound mixing was disregarded or considered as an afterthought. The soundscape starts strong, with the sound of the natural environment of Rio, along with the active streets allows the viewer to feel immersed. However, at some point in the film, we no longer hear much of this soundscape. The decision to only include music at the beginning and end of the film was deliberate but could have aided in moving the story along, as the lack of sound composition to support the story leaves the film feeling rather empty. As for the picture edit itself, the stories of the interviewees feel slightly out of sync. The film feels almost as if one is reading an anthology, with no clear direction of the placements of clips. There are quite a few subjects that were interviewed, but there is no sense of connection or flow with one another. Additionally, at some points, the b-roll had no clear connection to what was stated. Overall, it felt almost as if a lot of information was being hurled at the viewer, with no intention of fluidity and consistency. “The film feels almost as if I were reading an anthology, with no clear direction of the placements of footage." The cinematography feels rather dry. While this contributes to the grim concept of the film, this choice of lighting and colouring does not allow the film subjects to stand apart from their surroundings. In terms of content, there was a particular concern with the lack of infusion of Brazil’s connection to Haiti; their connection is pretty brief, and I believe that allowing more of a blend of both stories would allow for more dynamic compositions of the film. In sum, Right Now I Want to Scream is a film that effectively evokes themes of despair, life, loss, and mortality. This story proves that activism extends beyond the world that we know and are familiar with – Black people in other regions are also suffering from injustice and are chronically victim to the hands of police brutality. While the substandard technical elements heave potential to reduce the film, the content and message remain crystal clear: the revolution is alive everywhere. Editor’s Note: Right Now I Want to Scream: Police and Army Killings in Rio – The Brazil Haiti Connection screened at the Caribbean Tales Film Festival ’21, as part of the Shades of Intolerance programme.

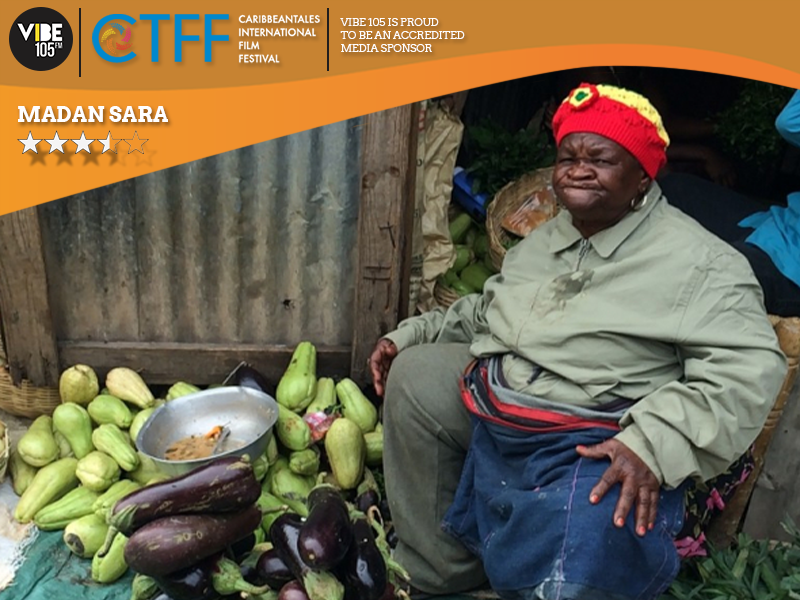

By Nelie Diverlus Haitian film Madan Sara premieres in Canada at the CaribbeanTales International Film Festival and centres around the economy in Haiti, informally upheld by Haitian women and their determination to provide for their families and communities. In this story, viewers can see various levels of frustration, disaster, and mistreatment that encompasses carrying the economy. This is a tale of outreach and revolution, ultimately teaching us what “all power to the people” truly defines. The film is mostly situated outside, taking the viewer on a trek through the streets of Haiti – guided by the sounds of its natural environment. Sounds of motor vehicles, people walking, and various conversations help bring the culture and nature of the film to life. The restless lifestyle is effectively portrayed through this immersive soundscape. While the soundtrack and soundscapes are captivating, it is rather important to mention the suboptimal sound mixing and recording. Various sounds of microphone shuffling can be heard, and the background music occasionally overpowers the voices of the subjects. At numerous points, cuts between music and voices within the interview is dissonant – the faulty blending of sounds takes away from the harmony of the story. Additionally, the music practically did not feel infused into the film – it is almost as if it was used as a placeholder, considering there were extended periods of time where there was no soundtrack accompanying the story, leaving it appearing slightly empty. As mentioned, the majority of the film is situated outdoors, allowing for the mise-en-scene to be filled with an abundance of greenery, flowy traditional dresses, and a large deal of natural lighting. As a result, at a few select points, we lose some subjects of the film to their surroundings. It was rather unfortunate to see at the rise of tension in the film, the subjects’ faces (those that are speaking, of course) are lost within the commotion of the streets. In addition to this, at times, the interviews conducted indoors have slight misplacement. While necessary to hear from these subjects, the tonal shift between the high energy of the streets of Haiti, to an office, feels slightly jarring. Allowing for smoother transitions between both settings would definitely maintain flow and consistency, as pattern is a distinct editing style within this story. “While necessary to hear from these subjects, the tonal shift between the high energy of the streets of Haiti, to an office, feels slightly jarring.” Madan Sara also plays on all four elements of matter – water, earth, air, and fire. The extinguishing of the fire ensued on the markets, in juxtaposition of the rubble left for the people to gather, illustrates the crushing of both dreams and realities. It is almost, quite literally, adding to the crushed spirits of those left behind to deal with the disastrous aftermath. The fire also symbolizes the blazing spirit of the Madan Sara; the demand for liberation and justice is a flame that does not die within this story. “The extinguishing of the fire ensued on the markets, in juxtaposition of the rubble left for the people to gather, illustrates the crushing of both dreams and realities.” An aspect that stood out greatly was an error in subtitling – most specifically when the subjects were speaking on the amount of money they lost. This simple error removes the honesty and raw truth that this story encapsulates. Perhaps this is a simple oversight to some, but an inaccuracy such as this has great potential to distort the narrative. With a story as disheartening as this, director Etant Dupain effectively constructs the building of prosperous futures, most specifically with the constant reiteration of these women working tirelessly to provide for their families, and for their children to create a fulfilling life for themselves. Concepts of dreams and aspirations is beautifully depicted within this feature, with a burning passion that will never die – similarly to the fiery spirits of the Madan Sara. Editor’s Note: Madan Sara screened at the Caribbean Tales Film Festival ’21, as part of the Bienvenue – Haitian Night programme.

By Nelie Diverlus A moving story of family, connection and community – the 16th annual CaribbeanTales opening night documentary Becoming A Queen teaches us about wins and losses, and the pressure that ensues with both concepts. The bright colours, rich textures, and an incredibly upbeat soundtrack are three distinct elements that bring the culture of the film to life. With its dive into rich history, along with the profound “passing the torch” narrative that is constantly proclaimed throughout, Becoming a Queen pays a magical, colourful homage to the ones who came before us. “Becoming a Queen pays a magical, colourful homage to the ones who came before us.” The story dives into Joella Chrichton, a woman striving to receive the title of Queen of Caribbean Carnival for the tenth and final time. Working with a creative team comprised of family certainly does not sound easy – and this film is proof. Differences of creative visions, deadlines and increasing insurmountable pressure placed on Joella to win continuously raises the stakes and tension that this documentary works to resolve. The viewer can share the feeling of adrenaline throughout the entirety of the film; the competition adds a level of stakes - often only attributed with fictional storytelling. "The competition adds a level of stakes that is often only attributed with fictional storytelling.” As far as technical elements go, Becoming a Queen sets the bar. Through meticulous detail, three of our senses are satisfied during the duration of the film: the texture draws us into the story by allowing us to almost feel the wardrobe; the glitter, gemstones and crystals all contribute to the compelling visual element of the film, and the incredible and catchy soundtrack keeps us engaged and alive. The life and invigoration of this film cannot be missed; the vibrant colours brighten the entire film, as well as effectively bring us into the world of carnival. Director Chris Strike’s decision to tie in history into this film is simply brilliant. The lineage of carnival is foreign to most, and by informing the viewers of it, the significance of this film is further projected, as the importance of upholding the tradition of carnival is now on us to remember. Perhaps unknowingly, this was another clever way of incorporating ourselves into the film. Freedom and expressionism are greatly portrayed with glimpses of history, whether through Joella’s family or not, as well as with various footage of people dancing with bright smiles and immense, contagious joy. The fiery spirit of carnival told through the lens of a seemingly soft protagonist is even more profound than we think. The choice of story told is a masterful portrayal of triumphs and defeats, and the raw human emotion that emerges from it. The authenticity that comes from telling a story surrounding a family deriving from an underrepresented island, living in an underrepresented district, is unmatched. Even if the rest of us haven’t competed in a Caribbean Carnival Competition, the film still speaks to us about what it means to work towards what we desire - not only despite where we come from, but also because of where we come from. It is safe to say that this film extends beyond our preconceived notions of Carnival. Seeing Black individuals living a free and authentic life of joy and expression is often torn away from us, and it was truly valuable to see us laughing, crying, frustrated, and joyful - genuinely, and wholeheartedly. With a bittersweet completion, Becoming a Queen shows us the importance of community, family, and passion in the midst of triumphs and defeats.

*Editor’s note: Becoming a Queen is the Opening Night title for Caribbean Tales Film Festival ‘21. |

Recent Posts

Categories

All

Archives

February 2022

|

|

GET THE APP!

Listen to VIBE 105 anywhere you go!

|

OUR STATION

|

TUNE IN RADIO

|

STAY CONNECTED

|

Copyright © 2021 Canadian Centre for Civic Media and Arts Development Inc. Except where otherwise noted, presentation of content on this site is protected by copyright law and redistribution without consent or written permission of the sponsor is strictly prohibited.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed