|

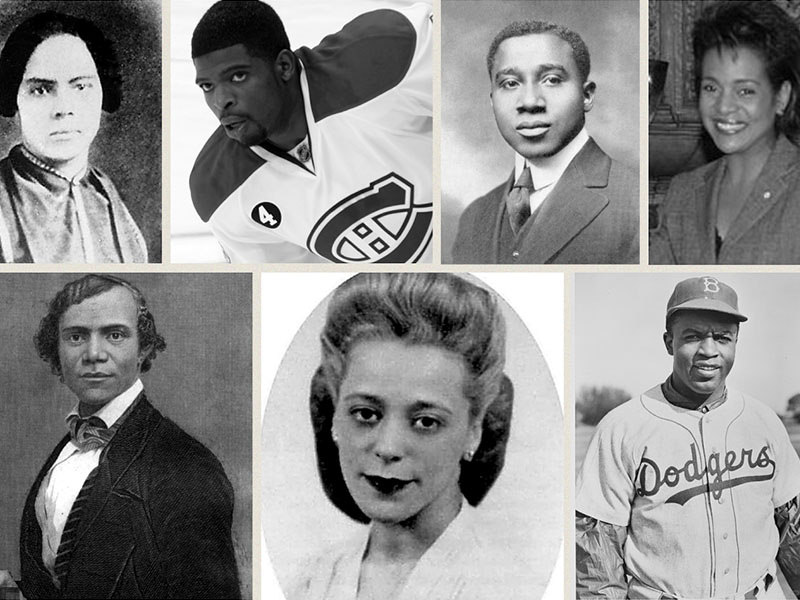

By Michael Asiffo Transcribed By Shira Ragosin Each year, during Black History Month, Canada celebrates the countless contributions and achievements of Black Canadians who have played an integral part, throughout history, in shaping the land’s heritage and identity. In this VIBE Talks interview, Correspondent Michael Asiffo speaks with Kamari Maxine Clarke - Professor of International and Global Studies, Carleton University about the Spirit of Black History Month. We discuss the importance of education, especially for youth, as well as explore the different ways in which Black History Month is celebrated around the world. Michael: What's the first thing you think of when it comes to Black History Month? Prof. Clarke: I think of multiple things, but I suppose the most important is education. The learning that happens during Black History Month, or at least that was the spirit around which the Black History Month initiative emerged. It was really about education. It was about introducing to people aspects of Black and African history that isn’t necessarily taught in the schools, so really education is what comes to me first when I think of Black History Month. Michael: You mentioned there education, and as a guy who’s not necessarily an expert, but obviously being black, you focus on Black History Month a couple times throughout the year. You always hear about the Martin Luther Kings, and the Rosa Parks, and the Muhammad Alis. But you never really hear about, for example, the movie Hidden Figures showed three brilliant black mathematicians. For you is there any unsung heroes who should kind of get a little bit more limelight during this time? Prof. Clarke: I have a two-prong way of answering that question, and often with my students this is the case as well. I would say that on one hand, there are a lot of people that fit the category of the Hidden Figures woman, the brilliant scientists that contribute to the transformation of our world, and fortunately, that story was popularized with the Hollywood movie. But there are a lot of other unsung heroes that we will never hear of. The stories that remain untold and the adages that really are stories, about things that we will never understand. And that aspect of the history really needs to be celebrated as well. The everyday people, the ordinary people. The people who sweep the floors, and who migrated, and sacrificed being with their kids so they could send back barrels and money every month so that their kids could eat back home, wherever home is. And so that's as much a part of our history as the brilliant scientists, who one day came to international attention. All of these stories have to be part of the ways that we reflect on what it is to be black in Canada. And these are stories that need to continue to be told, and even if nothing else, to reflect on. What does it mean to persevere through hardship, economic, political, social, etc. To reflect on it to celebrate it, to teach others about it. You know these are things that are important and that we have to continue to engage in. Michael: I kind of mentioned Hidden Figures accidentally, but it leads me to another point. I was talking to a friend about how I was planning on doing a Black History Month interview, and he went into the route of [saying] black people are usually known for the arts, sports, and a little bit of politics, obviously notably with Martin Luther King, and now President Obama, but not necessarily scientists. And he brought up the movie Hidden Figures, about how this was a thing in the 50s and 60s, and it’s now just coming to light in 2017. Do you agree with that point that when it comes to other fields, other than arts, and sports, and politics, black people don't really get their due? Or are you of the opinion that we usually celebrate everybody this time of month? Prof. Clarke: It's a tough question in some ways because in this period, of course, we’ve reached a point where post-affirmative action, especially in the U.S.A. and to some extent in Canada, we’ve achieved many things as people from the African diaspora who have had access to education, have had access to a range of possibilities and opportunities. But there’s still limits to what we’ve been able to achieve, especially in Canada. And so the reality is that a lot of people don't necessarily see themselves as representatives of black people. They might be scientists or engineers, etc. but many of them were born in Canada and see themselves as Canadians and they’ve pursued their dreams and become what they’ve become. So it’s complex in some ways because there are some high achieving folks who don't necessarily want to be identified or celebrated because of blackness. They want to be celebrated because they’ve achieved many things. And so part of it is being able to make it visible, whether they’re black or not, whether they want to be identified as such or not, that other people see what they’ve done, and they know that they too can do it. Especially children, especially young people. This realm of possibility, being able to see it so you can be it, is tremendous, especially for a young child. On one hand what I’m saying is that, there are many in many fields in science, and engineering, and computer programming, etc., who are black and don't get recognition, partly because they don’t want it, and then the other is because society may not celebrate them or know their story. The networks in Canada really aren’t the same as the networks in the U.S.A, for the black networks, the kind of alumni and associations, and the big money. It’s not quite the same, not that it doesn’t exist, but it’s very different, and so part of it is being able to identify those people, bring them back to high schools, to elementary schools, whoever they are, however they represent themselves and have them tell their story. We need more institutional structures that will allow that, if nothing else for young people to see that there are a lot of different people that are doing tremendous things out there. People from Ghana, from Nigeria, from Jamaica, from Barbados, born in Canada from Halifax, you know there all over and doing tremendous things and have been doing that. And so part of that is really to document and to celebrate by ensuring that the story is told. Michael: You mentioned something there along the lines of networks not being the same from U.S.A, for example, as opposed to say, Ghana. I would like to ask you, have you seen the effect of Black History Month differ in ways from USA to Kenya for example or Canada? Prof. Clarke: Yes I mean it’s tremendous in fact. While Black History Month is a part of Canadian celebrations, it really did have its birth, its institutional birth in the USA out of the Civil Rights Movements, and that was alongside Canadian formations that were deeply influenced by it and alongside it. And do in the USA it’s far more institutionalized. I lived in the USA for 28 years, before returning back to Canada, and I grew up in Toronto and left when I was 17 to go to university. And so in many ways I’ve been able to see both the developments, the early days in Canada and then to really come of age in the USA, to see how it’s taken shape and then to return home and get a sense of where things are, by way of black community, black organizing, the institutionalization of black stories, and black history. And so there's a big difference. In Kenya, it’s a very different situation, especially in places where black people are in the majority, and Ghana, and elsewhere. Black History Month, if it’s celebrated at all, it’s sort of a cultural celebration, there’s lots of things, a range of activities, but it certainly isn’t as widespread as the USA. So there’s a big difference, and in Canada it’s tremendously relevant. It’s not just Black History Month, like in the USA. we have a lot of different history months, a lot of different consciousness raising months. So if it’s Asian studies, or lesbian and gay and queer studies, there are a lot of different identities that are celebrated at different times of the year. So it’s like the USA you do have these cycles of recognition for history, for cultural engagement. So it’s in both sets of places as well as in Africa you see some of it, especially by those who are connected with diasporic blacks, who are in the UK, and in Canada, and the USA. But it’s certainly not the same and it's not as wide spread. And there are different issues at play. Michael: Are there any resources that anyone can go to get more information about what was talked about here? Prof. Clarke: Yes, tremendous. There’s reading novels, to textbooks, to books about feminism and Third World feminism, and there’s a lot that’s out there, it really depends on what the listeners are interested in. It’s vast. But people can check out my website, and my email address is there if people have questions, or want to follow up. My earlier work had to do with the African diaspora and how we understand these transnational religious practices, and in many ways much or what I’ve spoken about is very much informed by the work that I do. Now my current work is about international legal and transnational formation. So I look at international law, and the questions of African indictments by the International Court, and again how we understand the way that law travels and how the values around particular practices, particular notions of justice, are understood. So there’s a tremendous amount of information out there, a lot of books, a lot of writing that attempts to emphasize the importance of thinking about culture, history and race and politics. So there are many places to start, and one place is to look at my website and look at the work that I’ve done. To find out more about Kamari and her work, visit her website.

|

Recent Posts

Categories

All

Archives

February 2022

|

|

GET THE APP!

Listen to VIBE 105 anywhere you go!

|

OUR STATION

|

TUNE IN RADIO

|

STAY CONNECTED

|

Copyright © 2021 Canadian Centre for Civic Media and Arts Development Inc. Except where otherwise noted, presentation of content on this site is protected by copyright law and redistribution without consent or written permission of the sponsor is strictly prohibited.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed