|

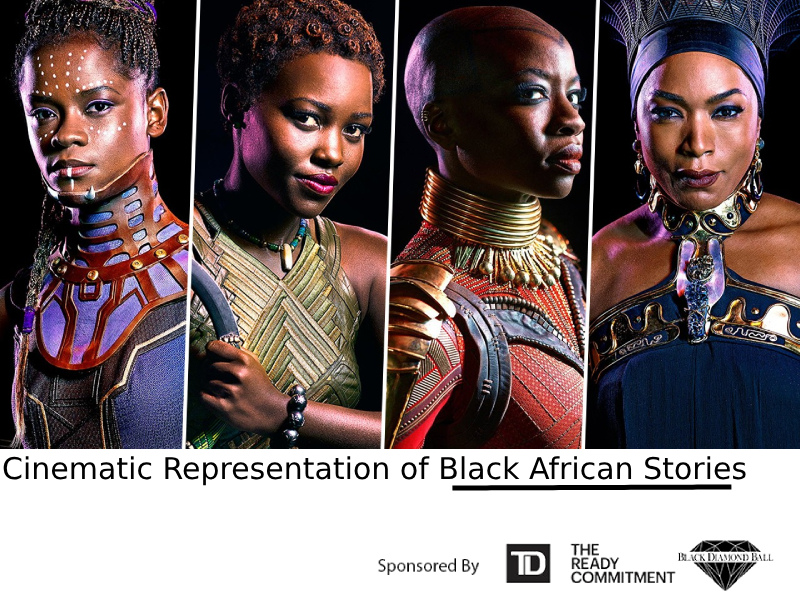

By Muniyra Douglas This narrative is always curated to an audience in a way that does not represent the full picture of any group of people, especially of African people. – Sylvia Bawa, Assistant Professor of Sociology, York University. In 2018, we saw one of the biggest cinematic films touch the silver screen, dominating theatres for weeks, social media feeds, blog sites and stir up some controversy, to the delight of Marvel fans. Black Panther presents Wakanda – a fictional African nation that invites positive, Black African representation and female empowerment without the interference of colonialism and European domination. The narrative is one that is often imagined but was yet to be fully visualized. While we may argue for the need of representation in the media and arts, do we understand why? How does the lack of representation affect the Black identity and the African diaspora? Professor Sylvia Bawa - Assistant Professor of Sociology, York University discusses with VIBE Correspondent Muniyra Douglas, the sociological and cultural impact of cinematic representation on the Black African community and the global audience. Muniyra: Tell us about your research. Prof. Sylvia: My research revolves around post colonial issues, women’s identity in sub-Saharan Africa and discourses around women’s empowerment and rights. What I also do is try to look at the discourses that depend on empowerment talk not only for African women, but also “developmental”, and how we’ve come to this space. The space that we have generally called the post-colonial era. However, it does not refer literally to post-colonialism because we know that the legacies of post-colonialism continue to endure. My work tries to look at those interesting spaces made by women, and the kinds of contestations that happen in terms of representation over and outside of the continent [of Africa]. Muniyra: How does cinematic representation shape the Black African identity? Prof. Sylvia: To a large extent, I think that is one of the biggest ways in which people have come to understand what blackness means. It reaches a very wide audience that text sometimes does not. It also allows people visually to have a sense of what it means to talk about blackness. This meant that traditionally and historically, especially in cinema and cinematic productions - that a lot of Africans and other people who have been misrepresented to a very large extent, have had to try to counter this narrative. This narrative is always curated to an audience in a way that does not represent the full picture of any group of people, especially of African people. And the space of the cinema is one of those spaces where these things are fought. Muniyra: Despite the progress made in implementing more positive representation, why do we still witness these same misrepresentations? Prof. Sylvia: These things have become an essential way in which people are socialized, especially in the North American and European society. We have been socialized to think about, look at and see Black people, or Africa as people and places typically inferior. And this happens right from Kindergarten, even daycare in some cases, and continues all throughout the curriculum. It can sometimes be very amorphous. You’re telling these children: ‘We have so much, and they [African children] have nothing.’ You’re teaching people who for years have had this notion of ‘saving’ Africa. The whole purpose of colonialization – whether here with Indigenous people or Africans – is just this idea that they are saving us from themselves. So, we are talking about several thousand years of this discourse playing out in our religious institutions, education, and politics. Muniyra: Does feminism have a place in the African diaspora? Or does it have to be reimagined for Black women? Prof. Sylvia: Yes, and yes. These days I prefer to use ‘feminisms’ in the plural. Because of the history, and the use of the term feminism and it being closely tied with the first-wave of feminism, and the issues of White, upper-middle class it is very difficult for feminism to diverse itself. But there are a lot of other misconceptions about Black or African feminists – we’ve always been feminists. In fact, there are lots of African feminist scholars that say talking about African women as feminists is kind of an oxymoron. But there has been significant pushback as you can imagine from people who don’t want to be associated with white, liberal feminism. They say: “If this is what feminism is, then I am not feminist.” Part of it is because African Black feminist or women may subscribe to feminist principles, but don’t use ‘the term’ because the term can be alienating to men or other communities. The misconception that has happened over the years is that feminism is about individual issues, instead it has traditionally tried to dismantle patriarchal systems and structures that oppress women. Muniyra: Talk about the success of Black Panther and the global acceptance of a more positive Black identity in cinematic films. Prof. Sylvia: This [superhero] market is huge and it’s a global market; and the demographic changes and shifts. And now, if you want to be successful [in cinema] you need to cater to the diverse audience and production team. Part of this is to say: You can’t have a movie with only white people – the whole world is filled with Black, Asian, Indigenous people and etcetera. Where is the representation of other people? If the story is so skewed, then we are not watching it. And in this way, we must learn to vote with our pockets. Black Panther is certainly not the first film to feature a strong, all-Black leading cast. However, the phenomena of the film’s success is certainly an amazing accomplishment. Cinematic representation has come a long way and isn’t still without its hiccups. However, if we continue to support artistic, cultural narratives it will keep these discussions open.

|

Recent Posts

Categories

All

Archives

February 2022

|

|

GET THE APP!

Listen to VIBE 105 anywhere you go!

|

OUR STATION

|

TUNE IN RADIO

|

STAY CONNECTED

|

Copyright © 2021 Canadian Centre for Civic Media and Arts Development Inc. Except where otherwise noted, presentation of content on this site is protected by copyright law and redistribution without consent or written permission of the sponsor is strictly prohibited.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed